In each market, there are participants with different objectives. Some look for long-term capital gains, some want to hedge their real positions, and still others try to make profits out of short-term price fluctuations. The concept of market making arises from such a market environment.

I. What is market making?

Market making means that a trader or a company puts both buy and sell orders into the market, and wait for people to trade with him on either sides. In every market, price is quoted with both a bid and an offer price, with the latter a little bit higher than the former. Ordinary traders and investors "take the market," buying at offer price and selling at bid price. However, market makers could sell at offer price and buy at bid price. For example, imagine that the last price of XYZ stock is 10.00 and a market maker puts a 9.90 buy order and a 10.10 sell order into the market simultaneously. If someone hits him by selling at his buying price of 9.90, he gets a long position. If he thinks that the price of XYZ stock would rise further, he would hold the position for a while and square it at a higher price. If he is neutral or even bearish, he may sell the stock right away. If the price in the next second is 9.92 Bid/ 9.95 Offer, he may make the market again by putting a sell order at 9.95 and wait for somebody to buy from him, or just sell at 9.92 to take the market. Market makers trade from market fluctuation to make money. They like volatile rather than one-sided markets. If the market keeps rising or falling, they will run into the problem of taking positions that are against most people. Market makers don't care much about the long-term trend, or fundamentals, but focus on the short periods of abnormal price movement. They trade hundreds or even thousands of round-turns every day, and accumulate small gains into big profits.

Recently, more and more automatic trading systems have come into the scene. Usually, market makers have a "seat" in an exchange, which is a kind of membership through which they can enjoy lower commission and faster access to the market. As electronic trading becomes more popular, it will replace the conventional exchange-based out-cry market. The out-cry market is the traditional market where traders stand in the pit and trade with each other through hand signals and out-cries. EUREX, the electronic trading system for European futures products, has shown great success and has become the number one futures exchange within just one year of its launch. Internet stock trading has also attracted a lot of people due to its low commission rates. In the electronic world, market makers are most welcome, since they provide greater liquidity to the market and make price moves smoother. In some equities electronic trading systems, such as Archipelago and Island, market makers can even receive commissions for each act of market making.

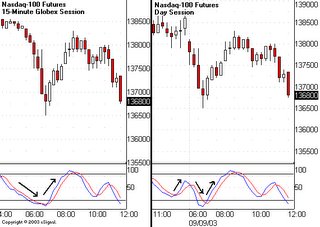

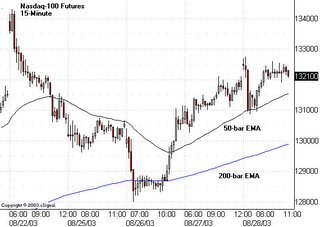

In the world of market making, "edge" is a key word. In the phrase "grasp the edge," edge means the difference between a security's real market price and its fair value. The task for market makers is to judge how much an edge would bring them both trading opportunities and profits. There are a lot of models and systems by which to judge the optimal edges. For example, if Cisco releases earning reports that are better than expected, market participants would jump into the market to buy Cisco stocks. Market makers would try to judge whether Cisco's stock price has risen too high in the most recent minutes through some fair-value models or chart analysis. If they believe that the price has been pushed high enough to justify a short-time retreat, they would begin to put sale orders into the market-with hopes that other traders would buy at their prices-and then square their short positions as soon as the expected retreat comes.

In the United States, market-making activities exist in all kinds of markets, especially in the market for futures. Chicago is the center of U.S. futures market. People trade commodities as well as financial futures here, among which equity index futures and U.S. treasury futures are the most active. The equity index future is a future contract based on the equity index, such as S&P 500, NASDAQ, and Dow Jones indices. It is calculated by adding the cost of carry, which is equal to the interest, and then subtracting the dividends payment from the current stock index. It is the best estimate of the future stock index, and provides great hedging and trading opportunities.

When a significant event happens, people enter the futures market first to buy or sell the index futures, and then the stock market follows. For example, at the time when Microsoft waited for the court decision on its anti-trust case, the trading of its stock was halted. When the decision came out, and while the trading of its stock was still suspended, people rushed into the NASDAQ future market to hedge their positions on Microsoft. In the stock market, there are restrictions on the short sale of stocks, and when the market is bearish, people have fewer opportunities to hedge, except through selling index futures, since the futures market treats buying and selling equally.

In the United States, the stock index futures market opens nearly 24 hours, except for a half an hour break. In contrast, the stock market only opens from 9:30am to 4:00pm. Though there is an off-hour market for stocks, only some big-name stocks such as Microsoft and Cisco have liquidity during off-hours. Therefore, if any pieces of news come out at night, investors can trade index futures to hedge or speculate on those less liquid stocks.

Many mutual fund managers use the index futures to manage their customers' asset. For example, imagine that a fund manager receives a call from a customer who would like to send him two million dollars to invest in the stock market in one month. However, the customer is quite bullish about the market, and is afraid that he may have to pay higher prices to buy stocks after one month. The fund manager can then buy one-month index futures contracts to lock in the entering price. No matter what happens, the customer can be guaranteed of the option of buying the index, or the portfolio of the index component stocks, at the price specified in the futures contracts after one month.

In 1999, one of the best years for the U.S. stock market, statistics show that nearly half of the stock investment funds could not beat the return of the S&P500 index after the management fees. That means, if you just bought the S&P500 index future, and held it for the year, you would get more than 20% annual return without paying attention to selecting high-performance stocks. Therefore, investment in the index futures is a very cost-effective method.

Furthermore, since the stock index is equivalent to the capital-weighted average of component stocks, buying index futures is just like buying a portfolio of the stocks but costs lower commission fees. Therefore, trading index futures is a very efficient way to trade the whole market.

III. Should China have an equity index futures market?

China desperately needs a stock index futures market to provide an efficient hedging method for investors. A lot of Chinese investors complain that the prices of their stocks get stuck even when the market index rises because no "dealers" ("Zhuang Jia") actively trade their stocks. Under such circumstances, if there were an index futures market, these investors would be able to buy index futures to take advantage of the bull market. Furthermore, when their stocks hit the down-limit and they cannot stop loss on their stocks, they could sell the index futures to approximately square their positions.

However, many people still remember the crash of the Chinese government bond futures market. As two major financial institutions fought with each other in the market, the prices of bond futures were pushed much too far away from the prices of the underlying bonds. Eventually, one of the institutions went bankrupt, and many small investors incurred great losses. Actually, there is a very efficient way to solve such problems. In every futures exchange in developed countries, there is a committee that is authorized to determine the close prices of futures contracts. They fix not only the futures market close prices, but also the cash market prices. When they believe that the futures prices have gone too far away from the cash market prices, they have the right to change the close price of futures based on the cash market price. It is the futures close price that determines the daily mark-to-market profit or loss on each account. Therefore, no one can take advantage by manipulating the futures price while disregarding the cash market price. Furthermore, the committee could also set the futures contract prices whenever an emergency arises. When the terrorist attacked the World Trade Center in the morning of September 11th, both index futures and some blue-chip stocks had been traded for a period of time in the pre-opening market. The stock and futures exchanges were forced to close after the tragedy. Due to the event, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) committee set the close price of the index futures on the 11th just equal to that of the 10th, and disregarded the pre-session trade activity. By doing so, the committee set up a fair beginning price for every stock and for all the investors when the market reopened later.

The major concern for the Chinese government regarding opening a futures exchange might be that the trading of futures is very speculative and risky. However, there might be an alternative way through which Chinese investors can take advantage of index products. In the United States, there are two synthetic stocks, QQQ and SPY, that are the cash stock version of NASDAQ and S&P500 index futures. Investors can trade such synthetic stocks as real one, thereby eliminating the need to use leverage as with index futures. Therefore, the synthetic stocks are more for hedging purposes than for speculative uses. So if the index futures market is thought to be too risky, Chinese stock market could establish two synthetic stocks that represent the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock indices for investors to invest in and to hedge their individual stock positions.

The equity index futures market has proven to be both an effective and an efficient supplement to the stock market. As Chinese financial market develops, market making will become an important part of its functions, and an equity futures market should become an integral component.

(The author is a Trading Strategist on the index futures at the Global Electronic Trading Company (GETCO) in the Chicago Board of Trade.)

Market Making and the Index Futures Market

Tags: market making, market maker, spread, futures,